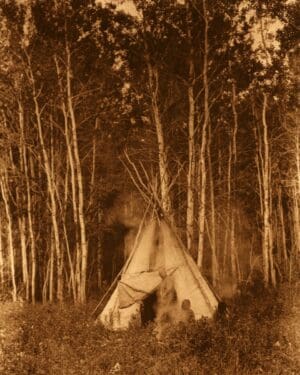

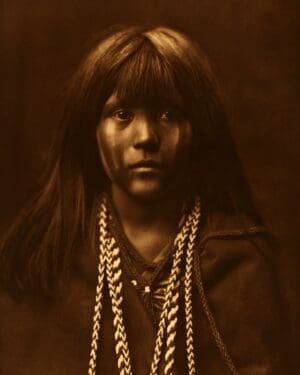

Chipewyan Native Americans

Chipewyan Indian Photos by Edward S. Curtis

Tribal Summary

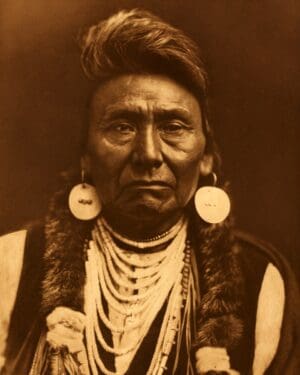

Dress

The distinctive garment of all northern Athabascans, both men and women, was the parka, a sleeved shirt with the skirt cut to a point behind and before. The material was caribou-skins, dressed on both sides for summer wear, tanned “in the hair” for winter. The winter garment was also hooded, and hare-skin mittens were either sewed to the sleeves or attached to a cord passing across the neck of the wearer. Leggings of men came to the hip in the Plains fashion, those of women to the knee. The moose-hide and caribou-skin moccasins had separate soles slightly upturned at the edge. Fur robes were of course indispensable. According to Hearne, “it requires the prime pans of the skins of from eight to ten deer to make a complete suit of warm clothing for a grown person during the Winter: all of which should, if possible, be killed in the month of August, or early in September.”

The hair of both sexes was cut at the level of the eyes, and hung unconfined. Early observers noted parallel blue or black bars tattooed on the cheeks of members of various northern Athapascan tribes.

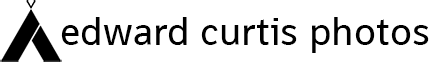

Dwellings

Chipewyan lodges were conical tipis constructed in the usual manner of poles covered with caribou-skins. The sweat-lodge was unknown.

Food

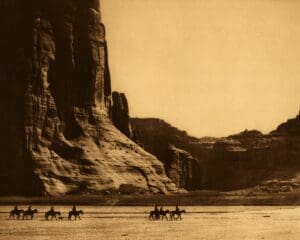

The principal game animal was the caribou, the Chipewyan name of which signifies “flesh.” During the spring and autumn migration of the vast herds to and from the Arctic feeding grounds great numbers were easily killed by spearsmen in narrow defiles or at water crossings. In summer caribou were driven into large enclosures, there to become entangled in thong snares; they were crowded down a peninsula and into the surrounding water; they were approached by a pair of hunters, tandem, bearing the horns and head-skin of a caribou and imitating its peculiar movements.

Moose are still numerous, and during the mating season are successfully lured within gunshot by means of a birch-bark trumpet with which the hunter imitates the voice of either bull or cow. Rawhide snares attached to resilient saplings were formerly much used for this animal, as well as for woodland caribou. The surest but most laborious method was to run the moose down when deep snow impeded it.

Beaver were important to the northern tribes even before the traders created a demand for their skins. They were captured by barring them in their huts, opening the roof, and spearing them; by breaching a beaver-dam and hooking an investigating animal on a caribou-antler gaff; by setting a bag-net below a breach in the dam. They were speared also in their refuges under the banks of streams.

The fourth important game animal was the hare, which was and is taken in noose snares.

The woodland buffalo was not unknown, but was unimportant.

Waterfowl swarmed in the marshy lakes and were shot with arrows and caught in snares set at the nests or between parallel fences built out at right angles from the shore.

Fish – principally maskinonge, lake trout, and whitefish – were and are a prime staple. They were taken at all seasons with bone-pointed spears, antler gorge-hooks, and gill-nets.

Vegetal foods were of comparatively little importance to the tribes of the far north but in the southerly Chipewyan area such products occur in fair abundance. Besides two species of blueberries, two of cranberries, and service-berries, various other fruits, were harvested, and cattail-roots, tule root-stalks, bast from the bark of aspens and pines, and lichens were universally held in regard.

Showing the single result